In May 2025, EuroClio and Europeana welcomed six cultural heritage educators to The Hague for a co-creation session as part of ‘Creating Lessons with Cultural Heritage’. The project seeks to dive into the untapped wealth of cultural heritage available through museums, archives and other cultural institutions to create ready-to-use materials for the classroom.

During their stay, the educators co-created eLearning activities using the Historiana platform. Below, Farilyann Muzo, educator at the Nationaal Archief, shares her experience of working with digital cultural heritage and introduces her eLearning teaching activity.

- Link to the eLearning activity: http://hi.st/BrF

Teaching with primary sources and archival material allows students to engage directly with the past. Not just to learn about history, but to analyze how it was recorded, preserved, and framed. In doing so, they begin to understand that archives are not neutral mirrors of the past, but constructed narratives shaped by power and omission. This eLearning activity, developed for EuroClio in partnership with Europeana, challenges students to confront the authority of written documents by engaging critically with cultural heritage. By focusing on the 1795 Tula Uprising on Curaçao, this module guides students to recognize whose stories are preserved—and whose are hidden.

Work with Cultural Heritage?

Cultural heritage connects us tangibly to our past. Whether physical artifacts, digitized collections, or archival documents, heritage holds stories of human experience. But these stories often reflect power hierarchies: archives were built by authorities such as governments, church officials, plantation owners who decided what was worth keeping. As a result, voices from marginalized communities are often excluded.

Gregory Ashworth has emphasized that heritage is not merely the past; it is the present interpretation of the past: “the contemporary use of the past.” When students encounter cultural heritage, they engage in a dynamic dialogue—not only discovering what was preserved, but also questioning why something was selected or excluded.

By working with real heritage—primary sources from colonial archives—students do more than consume history. They experience its complexity, question who wrote it, and begin to recover what was intentionally or unintentionally erased.

Strategies and Learning Methods

In the eLearning activity Tula’s 1795 uprising is used as a case to question archival authority. On 17 August 1795, Tula, an enslaved man on the Dutch island of Curaçao, led roughly fifty fellow enslaved people in refusing further forced labor. Rallying hundreds more as they moved from plantation to plantation, they invoked the French Revolution’s ideals of liberty and equality. After about a month the colonial authorities crushed the movement and executed Tula, yet his revolt endures as a landmark act of resistance, now commemorated each year as Curaçao’s “Day of the Fight for Freedom.” The e-learning introduces students to documents written by Jacobus Schinck, a Catholic priest, Baron van Westerholt, a military officer and Pieter Theodorus van Teylingen, the prosecutor on the case.

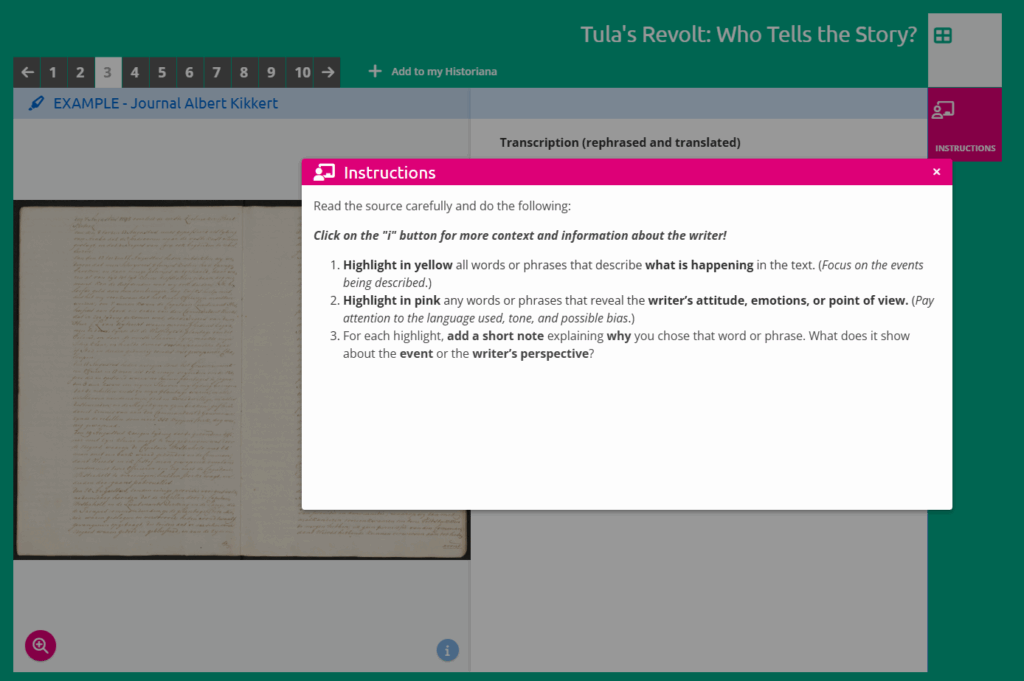

These sources describe Tula’s leadership, demands for basic rights, and suppression by colonial forces. But their framings using words like “rebels,” the “n-word,” and “murderous gang” offer a limited lens. Students are prompted to think about:

- Who is speaking?

- Whose interest does the document protect?

- Whose voices are completely missing?

By guiding learners through targeted questions, the module encourages them to look between the lines and reflect on archival omissions, especially the vanishing voices of enslaved people themselves. This step is the foundation for deeper inquiry: before imagining other perspectives, students must first recognize whose stories are absent.

While the current module focuses on recognizing included and missing voices, a next step would be to invite students to fill the archival gaps. This is where Saidiya Hartman’s concept of critical fabulation comes in. Hartman wrote about creating “an impossible story that attempts to say that which resists being said” and using imagination to amplify the impossibility of complete archival representation.

Hartman’s methodology urges historians to narrate “with and against the archive,” combining fact and speculation ethically. In this next step, students would be asked to write short imagined narratives. Voices of individuals who could not record their own experiences. These narratives would be grounded in contextual clues: locations, social roles, emotional tone etc. By doing so, students learn to balance: historical evidence (archival grounding), Reflective interpretation (what might have been) and contemporary ethical stance (avoiding dehumanization).

Ethical Considerations

When teaching about violent colonial pasts, educators must navigate a fine line. On one side lies historical accuracy; verifying facts and contexts. On the other is present-day sensitivity; ensuring we don’t replicate the archive’s violence. For example, although colonial sources often used racist terms, we choose not to repeat them verbatim in e-learning modules. They are transcribed with placeholders, and students should be encouraged to use respectful terminology (e.g., “enslaved people” or “people of African descent”) .

This approach reflects Gregory Ashworth’s insight: heritage is “the contemporary use of the past.” We interpret our inheritance with today’s moral frameworks. By making these choices explicit, we model responsible scholarship and empathy.

Broad Applicability

Although rooted in Tula’s revolt, the module’s method is scalable to any archive shaped by power. Museums, universities and state archives all contain records by gatekeepers. These archives inherently marginalize voices of opposition, resistance, and different identities. By teaching students to align the archive’s visible voices against the missing voices, we equip them with tools to question historical authority.

Understanding that heritage is both what remains and what is omitted empowers critical citizenship. It invites students to ask: What if my story isn’t captured? How could I add it? What new questions can I ask to reshape my understanding of history and the present?

Conclusion: Active Engagement with Heritage

This eLearning activity is not about memorizing facts from 1795. It is about developing critical learners. Students who ask: Who wrote this? Who decided it mattered? What voices are missing? The module’s initial phase empowers learners to observe archival bias. In a next stage it could offer them a creative yet grounded opportunity to participate in the making of history. As they imagine unheard voices, they engage with archives not merely as passive consumers, but as active co-creators.

Cultural heritage, especially when handled with reflexivity and care, can be a powerful classroom catalyst. It helps students understand where they come from, how narratives get built, and where gaps might lie. Most importantly, it compels learners to ask: What stories will they leave behind, and who gets to hear them?