I often wonder what growing up in 2025 is like. I myself went to school during the late eighties and early nineties, when the Berlin Wall, and consequently the Soviet Union fell. Despite, or perhaps because of, a swift war in Iraq, I experienced a hope for a better future. A hope that may best be voiced in Fukuyama’s idea of ‘the end of history;’ from then on, the world would know more peace and prosperity than the decades that came before. During current-day interviews with Dutch high school students, which is part of my own research, this hope seems to have diminished. Students worry about the future, especially about polarisation, discrimination, their economic possibilities and foremost about the environment. Other and earlier studies have acknowledged similar views of the future among students (Béneker, 2018). With the growing ecological crisis and several wars happening now, we as teachers may understand the worries of our students: what will the world they will grow up in look like and how will their lives be affected?

History and meaning

Such concerns play a role within the history classroom. As the German scholar Jörn Rüsen has argued, history is always future-oriented, if not explicitly, then at least implicitly. By understanding how the present is caused by changes in the past, people try to imagine what we may expect from the future. Such an understanding is not a neutral one, but one that is grounded in core values and more encompassing worldviews. Our stories of the past, especially those shared outside of schools, tell us not only how this world came to be, but also how this world works and what is of value. They help us orientate ourselves, both in time – ‘How much personal freedom do I have compared to my grandparents and how did this change occur ?, Will our world still be inhabitable in the (near) future?’ – as well in life – ‘Why does history tell us about how we should treat minorities?, ‘How can we best protect democracy?’. Shared stories and understanding of the past, thus, helps us to give meaning to our lives. Because of this, people may often experience emotions when listening to, sharing or even studying such stories.

Heritage as source for meaning.

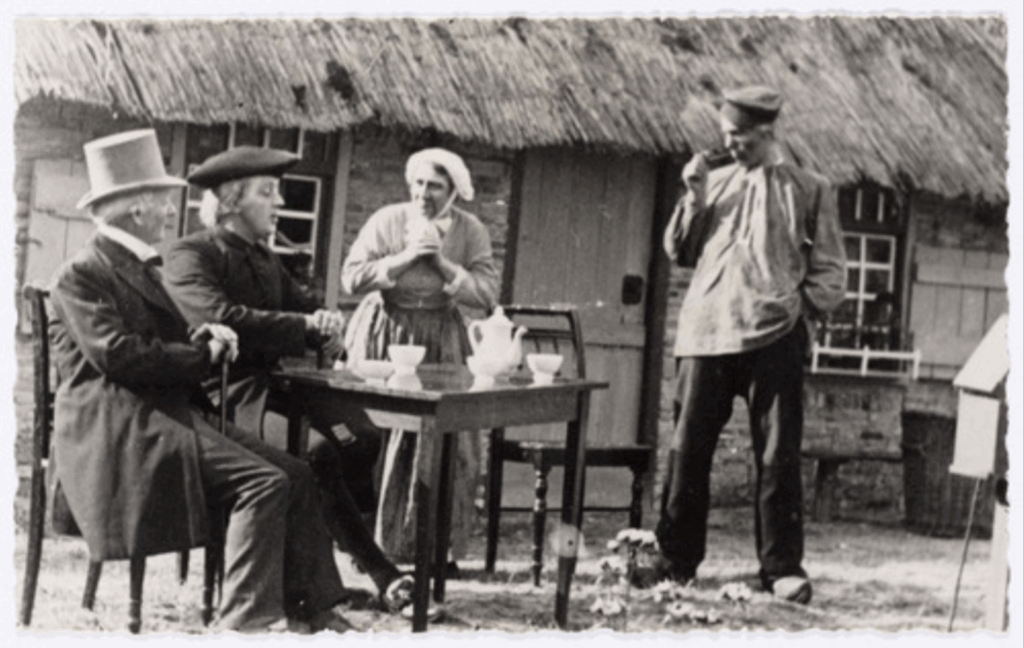

An important source of such stories may be heritage. Heritage, understood as a dynamic, though meaningful relation with the past, connects us to our forebears, to a social group or culture that precedes our own life. And heritage may provoke strong emotions. Let me give an example from my own hometown Tilburg: Peerke Donders. Peerke (Peter in our local dialect), was the son of a small weaver. Although from a very modest background he was admitted to a Catholic Seminary because of his religious zeal. After his ordination he went to Surinam, where he worked at a leper colony. There he served mostly enslaved people, often sent away for plantations, for the rest of his life. In Tilburg, he is considered somewhat as a local hero, the archetypical inhabitant of the city: a Roman Catholic son of a labourer, who worked hard to relieve the suffering of others. In this part of the Netherlands, Peerke spoke to the local population, who considered him to be the source of miracles. His life story became an important source of inspiration. It even became the subject of popular plays, like the one in figure 1.

When Tilburg industrialized rapidly in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, local clergy, politicians, and chiefs of industry saw in him the perfect mascot to challenge socialism. Peerke’s life showed that taking care of the underprivileged was not reserved for socialists. Being an industrious Catholic worker, while taking care of others, was presented as a core characteristic of local identity. His life story became an important source of inspiration. It even became the subject of popular plays, like the one in figure 1.

Figure 1: play of the life of Peerke Donders (Europeana Digital Archive)

To strengthen this image, a statue of Peerke was erected (see fig.2). The fact that Tilburg was liberated from German on his birthday added to his veneration.

Figure 2: The statue of Peerke Donders

Sensitive heritage

The last couple of years, Peerke and, more specifically, his statue has sparked significant commotion. When you look at the statue, the underlying colonial ideas are quite evident. Peerke is standing above a man, clearly from African descent, who is shown in rags. The African is being blessed by Peerke, stressing the hierarchical relation between the two; the White Peerke is portrayed as clearly superior. Furthermore, Peerke’s personal correspondence showed that although he sincerely served the people with leprosy, he also explicitly disapproved of their native religious practices, actively destroying them. Peerke’s history is therefore integrally connected to the Dutch colonial history and all the abuse that it entailed. It is therefore understandable that some people experience negative emotions towards Peerke, his story, and his statue. People with personal ties to that colonial history, especially those whose ancestors suffered from it, still experience hurt when encountering Peerke. A court procedure was therefore started to remove the statue altogether. Other inhabitants thought this was a denial of their history.

Sensitive topics and emotions in the classroom

In other European Countries similar discussions were held in the last decade. They seem to refer to students’ worries about polarisation. At the same time, they show that history is often an emotional endeavour. Such emotions play a role in the history classroom as well. In my research I observed a lesson on the historical use of the term ‘enslaved.’ The teacher asked the class If they would agree that using this term was preferable to the term ‘slave’ to describe enslaved people in our Dutch colonial history. The class debate at one point became quite heated, although luckily it remained respectful, when students whose ancestors were in fact once enslaved argued that the term ‘slave’ did not do justice to those ancestors. They felt the need to explain that they found this term improper. Others did not seem to mind what term was used. For them, the difference in connotation seemed to be limited.

In order to study history, we as history teachers need to take these emotions seriously. We might be seduced in thinking that history is a neutral affair, and that emotions should not play any part in studying the past. Although I consider the training of historical, rational, thinking skills to be an essential goal of history education, thinking that history can be purely neutral for students would in my opinion be a misunderstanding. If history wants to help students orient themselves meaningfully in life, the emotional element should be integrated into our teaching. Using heritage, especially contested heritage, may be a good starting point. My suggestion is to let students voice those emotions in what would be called a ‘brave space,’ a space that encourages individuals to engage in courageous conversations, confront biases, and challenge perspectives constructively. This means that we would start with emotions, while possibly using different strategies than we would normally do as history teachers. One activity that works well is that of emotion-networking. When emotions are explored as a class, we could determine the questions we would like to ask concerning the heritage object and how we would take the emotions into consideration while answering them.

History as source for faith

Students may experience similar emotions when discussing other sensitive issues, like the environment or the war in the Middle East for example. These emotions are proof that they care about and are meaningfully involved in this world. By discussing these, we can give students the confidence that they are able to understand emotionally laden subjects, without resorting to polarizing views. Coming from the second school subject I teach, Religious Education, I would argue that we give them faith. With faith I do not refer to a set of dogmas or beliefs, but a deep confidence that when they are open-minded to each other and willing to deliberate issues, they are able to deal with the considerable problems our world is facing. They need for such deliberation has recently been stressed by Keith Barton & Li-Chin Ho in their book Curriculum for Justice and Harmony. Deliberation, Knowledge, and Action in Social and Civic Education (2022), which is highly recommended.

In this, heritage may also play another role. Heritage may provide us with examples of how our ancestors addressed similar issues. In the Netherlands, our water management, which goes back centuries, may be of interest for example, especially because our solution to our water problem often required cooperation. How did earlier generations get people to collaborate? Another example may be earlier ways of effectively using energy, like earlier and more eco-friendly ways of isolating houses, which appear to be more effective and long-lasting. A final example can be found on the Europeana website: different heritage objects related to diversity and inclusion.

The world in 2025 is a different world than it was in 1995, when I graduated from high school. Because of the different challenges facing us at this moment, students may experience a more emotional relation to the world, and therefore also to the past. Heritage can certainly bring about an emotional experience. These emotions are a part of what makes our relationship to the past meaningful. I would advise integrating those in our teaching, while still focusing on historical thinking skills. At the same time, Heritage may help us to reflect on our present, provide confidence in our human agency and therefore give faith to our students that by openly deliberating issues together, using the wisdom of our forefathers, they are able to meet those challenges. Luckily, heritage is often easily available, for example in the wide collections of Europeana. In some cases, this material has already even been adapted to teaching materials, which can be found on the Historiana website.

References

Béneker, T. 2018. Toekomstgericht onderwijs in de mens-en-maatschappijvakken. LEMM expertisecentrum-mmv.nl/wp-content/uploads/Beneker_2018_Toekomstgericht-onderwijs.pdf#page=20.10

Barton, K. & Ho, L-C. 2022. Curriculum for Justice and Harmony. Deliberation, Knowledge, and Action in Social and Civic Education. Routledge