In May 2025, EuroClio and Europeana welcomed six cultural heritage educators to The Hague for a co-creation session as part of ‘Creating Lessons with Cultural Heritage’. The project seeks to dive into the untapped wealth of cultural heritage available through museums, archives and other cultural institutions to create ready-to-use materials for the classroom.

During their stay, the educators co-created eLearning activities using the Historiana platform. Below, Dr Caitríona Ní Cassaithe shares her experience of working with digital cultural heritage and introduces her eLearning teaching activity.

- Link to the eLearning activity: http://hi.st/Brf

Introduction

As climate and ecological crises intensify, educators face the urgent challenge of preparing students to engage with these complex issues intellectually, emotionally and ethically. However, climate change education often proves difficult and unsettling for both teachers and students because it demands confronting complex scientific information alongside the emotional weight of potential future impacts and the challenges of societal inaction. So how can we, as history educators, use history to navigate what can be difficult and unsettling knowledge in age-appropriate yet effective ways? This blogpost explores how digital cultural heritage resources, particularly digitised archives, can be used to teach ecological history through the lens of Traditional Medical Knowledge (TMK). It describes a classroom activity that allows students to explore, through historical enquiry, traditional wisdom relating to healing plants.

What is Traditional Knowledge?

Traditional Knowledge, often used interchangeably with terms like Indigenous Knowledge, Local Knowledge and Folk Knowledge, refers to the accumulated body of knowledge, know-how, practices and skills that have been developed and passed down from generation to generation within a community (Onyancha, 2022). Traditional Knowledge is inherently contextual and place-based and reflects a worldview that views humans as an integral part of nature rather than separate from it. Built on direct experience and observation of the natural world over time, it is primarily transmitted orally through stories, songs, rituals and practical teachings related to areas such as agriculture, medicine and environmental stewardship (International Council for Science 2002).

Why does Traditional Knowledge Matter?

In the last few decades, there has been a growing appreciation of the important role Traditional Knowledge plays in sustainable development, biodiversity conservation and the understanding of complex ecological systems. For example, The Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) program, established by UNESCO recognises the importance of traditional knowledge in addressing global challenges such as biodiversity loss and climate change. Yet despite its relevance to sustainable practices, traditional knowledge has been marginalised in many formal educational contexts (Kavanagh & Ní Cassaithe, 2024). In this blogpost, one form of Traditional Knowledge – Traditional Medical Knowledge, is discussed as an entry point into teaching and learning about sustainable living.

What is Traditional Medical Knowledge?

For thousands of years, traditional medicinal plants have been used to heal and support wellbeing. Long before modern medicine, our ancestors looked to the land for remedies, learning which leaves, roots, barks and flowers could treat wounds or digestive problems. Nature was their very own pharmacy and this knowledge came from deep observation and a strong connection to the natural world. Unfortunately, today this knowledge is fading and fewer and fewer people know about healing plants (or even their names) and some of the stories and languages that carry this wisdom are disappearing too.

Learning about Traditional Medical Knowledge, especially knowledge involving plants and herbs, can help students grasp the importance of sustainability and a respect for biodiversity and the natural world. Exploring the reliance on local plants for medicine in the past can allow students to appreciate the benefits of living in harmony with nature in the present (Kavanagh & Ní Cassaithe, 2024).

This holistic perspective, often marginalised by Euro-Western influences and capitalist mindsets that prioritise extraction and commodification (Kavanagh & Ní Cassaithe, 2024), teaches students that human health is inextricably linked to ecological health thereby cultivating a sense of stewardship for the environment and promoting sustainable living from a young age.

Our growing disconnection to the natural world

One of the most evident examples of our growing disconnection to the natural world is the increasing urbanisation of global populations with more and more people living in cities and further away from undeveloped natural areas. This shift means less direct access to green spaces and diminished opportunities for daily interactions with nature. Coupled with this is the proliferation of digital technology and screen time which has dramatically altered how children and adults spend their leisure hours. These changes in lifestyle and concerns over safety mean fewer opportunities for unstructured, free play outdoors. Consequently, some children may lack the fundamental experiences that build a deep connection with the natural environment (Beery et al., 2023).

One of the challenges in fostering ecological awareness is a phenomenon known as plant blindness – a proposed cognitive bias describing the tendency of people, especially in industrialised societies, to overlook plants in their environment and undervalue their ecological importance (Wandersee & Schussler, 1999). This phenomenon manifests in various ways which include: failing to notice plants in one’s immediate surroundings, not recognising their critical importance to the entire biosphere and human existence, viewing plants as inferior to animals or being unable to appreciate their unique features and aesthetic qualities. Research has shown that both students and the general public identify plant species more poorly than animal ones and have a weaker knowledge of the properties and uses of plants (Bebbington, 2005; Zani & Low, 2022). This cognitive bias not only contributes to environmental neglect but also reinforces disconnection from traditional plant knowledge and the crucial role plants play in sustaining life.

By engaging students with historical archives and traditional medical knowledge, this activity can help counteract plant blindness and nurture a deeper appreciation and respect for biodiversity and the interdependence of all life forms. Additionally, learning about traditional medicine across different communities can introduce students to cultural diversity and deepen their appreciation for the wisdom passed down through generations.

Why work with Digital Cultural Heritage?

Digital cultural heritage quite literally brings the voices of the past into the present. By working with digitised archives, students can engage directly with the memories, beliefs and knowledge of ordinary people across time. Using digital cultural heritage resources in the classroom can encourage active historical enquiry through interpretation of primary sources. They can also connect students with intergenerational memory and oral traditions to create a bridge between the past and contemporary consciousness by expanding their understanding of what is valued as “history”.

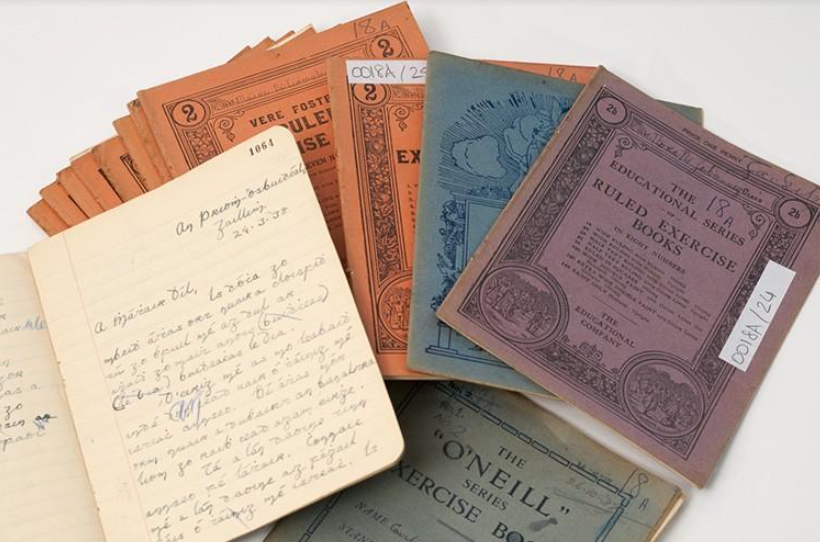

The digital archive selected for use in this activity, The Schools’ Folklore Collection from Ireland, is particularly suitable for classroom use. The Schools’ Folklore Collection was curated from an innovative project undertaken by the Irish Folklore Commission between 1937 and 1939. During this time, over 50,000 Irish primary school children were tasked with collecting local history, folklore and oral traditions from their parents, grandparents and other older community members. Guided by their teachers and special handbooks, they meticulously recorded these stories, customs, proverbs, local cures, historical accounts and games and crafts, often in their own handwriting, creating over 750,000 pages of invaluable material. Now digitised and accessible online through platforms like dúchas.ie, this collection provides an unparalleled window into life in the early 20th century.

Learning how archives function can demystify the process of historical research as students gain insight into how historical information is collected, organised, preserved and made accessible. Through working with archival materials, they learn about the selection process involved in creating archives (what gets kept, what doesn’t and why) which introduces the idea that historical records are not exhaustive but represent conscious choices and efforts. Understanding how digital tools preserve oral traditions also highlights the ongoing evolution of historical methodology and the importance of adapting to new technologies to safeguard our intangible heritage.

Teaching Strategy: Historical Enquiry

This activity is grounded in the Historical Enquiry Framework developed by Ní Cassaithe (2020, 2025) which supports students in working as historians through five key stages: generating questions, gathering evidence, analysing evidence, creating evidence-based arguments and reflecting and connecting to the present.

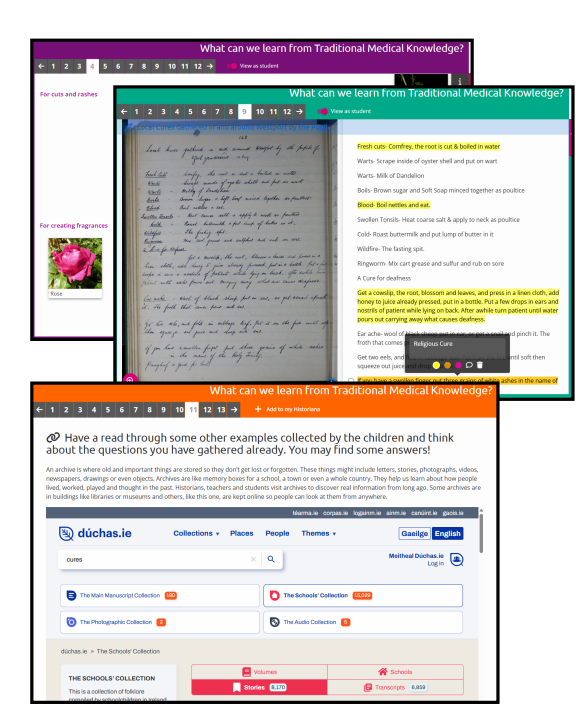

At the outset, students are introduced to the core inquiry question “What can we learn from Traditional Medical Knowledge?” and can develop their own sub-questions that they may like to explore on this topic themselves. They then are provided with evidence from a range of historical sources, including digitised folklore archives (www.duchas.ie), plant photographs (sourced from the Wellcome Collection at www.europeana.eu/en) to help answer those questions. In the next phase, they analyse evidence by categorising cures, interpreting beliefs and comparing traditional practices. Students are encouraged to synthesise their findings to develop arguments about how traditional knowledge was used and why it mattered. Finally, they reflect and connect to the present by considering the ecological relevance of TMK and how traditional approaches to healing and sustainability might inform how we live today.

Overview of the eLearning Activity

This multi-stage activity combines digital sources, critical thinking and community engagement to explore TMK.

1. Introduction to TMK and Plant Knowledge

Students begin by learning how traditional cultures used plants for healing. They explore the holistic worldviews that shape TMK and emphasise balance with the Earth and sustainable harvesting. By engaging with this activity, students can experience how people in the past often held worldviews fundamentally different from modern ones. This introduces the idea of diverse human experiences and knowledge systems and implicitly teaches them to avoid presentism (judging the past solely by present-day standards) and encourage them to understand past actions within their own contexts.

2. Plant Identification and Matching

Students receive photographs of eight common healing plants to sort them into “known” and “unknown” categories. They then match each plant to its traditional cure (e.g., lavender for sleep) and check and reflect on their answers.

Through naming and identifying plants and learning about their traditional uses, students learn to recognise the importance of plants and also explore how historical communities interacted with and understood their natural environment. It moves their experiences of history beyond abstract dates and narratives to reveal tangible, practical aspects of daily life and survival that illustrate how history is not just about grand events but also about how people lived in the past.

3. Exploring the Schools’ Folklore Collection

Using excerpts from the folklore collection, students use the highlight and annotation tools to identify and create new categories (such as religious, magical or ritual-based cures). As a class, they can compare findings and discuss patterns in beliefs and practices.

In this activity, students engage with the nature of historical evidence by directly handling (digitally, in this case) handwritten historical documents. They learn that historical evidence isn’t always neat and typed; it can be messy, personal and require interpretation (e.g., deciphering handwriting, understanding regional turns of phrase). Annotating these excerpts teaches them to analyse sources, identify key information, decipher cultural nuances and shows them that history is constructed from an analysis of fragments of the past.

4. Understanding Archives

Students then learn what an archive is and how it preserves cultural memory. They are given a link to explore the digital collection further and can choose new cures to analyse and share with classmates.

5. Oral History Interviews

Students conduct interviews with family or community members to uncover traditional cures remembered or still used today. In this activity they learn how to ask respectful questions and to record answers and reflections to create a “mini folklore archive” of their own.

This activity transforms students from passive learners into active historians. By collecting stories from family or community members, they create their own “mini-archive,” directly experiencing the process of creating historical knowledge. They learn that history is not just found in books but is alive in people’s memories. This activity highlights the importance of testimony and lived experience as valid forms of historical evidence which are often overlooked in traditional historical curricula focused solely on written documents.

6. Creating a Herbal First Aid Kit

To consolidate their learning, students are asked to design a Herbal First Aid Kit for their school. This could be a physical, artistic or virtual one. In this activity, they choose traditional remedies based on their research, explain what each is used for and how it was traditionally prepared.

This culminating activity allows students to synthesise their historical research and apply it in a practical, creative way. It demonstrates how historical knowledge can have contemporary relevance and value.

Conclusion

Integrating the historical study of plants and their healing properties into children’s education offers a unique and powerful way to engage them in a deeper understanding of the world around them. By exploring Traditional Medical Knowledge, students not only connect with the ingenuity and resilience of past cultures but also gain an appreciation for the interconnectedness of human well-being and the natural environment. This historical lens helps them to understand the origins of sustainability and to recognise that responsible stewardship of plant resources was, and still remains vital for health and survival.

References

Bebbington, A. (2005). The ability of A-level students to name plants. Journal of Biological Education, 39(2), 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2005.9655963

Beery, T., Stahl Olafsson, A., Gentin, S., Maurer, M., Stålhammar, S., Albert, C., … & Raymond, C. (2023). Disconnection from nature: Expanding our understanding of human–nature relations. People and Nature, 5(2).

International Council for Science (2002). Science and Traditional Knowledge: Report from the ICSU Study Group on Science and Traditional Knowledge

Kavanagh, A.M. & Ní Cassaithe, C. (2024). Seeing the world through alternative eyes: Using Indigenous stories and knowledge to teach about socio-ecological issues. In A. Allen, A.M. Kavanagh & C. Ní Cassaithe (Eds.). Beyond single stories: Changing narratives for a changing world. Information Age Publishers.

Ní Cassaithe, C. (2020) “Which is the truth? It’s actually both of them”: a design-based teaching experiment using learning trajectories to enhance Irish primary children’s epistemic beliefs about history. PhD thesis. https://doras.dcu.ie/24663/

Ní Cassaithe, C. & Waldron, F. (2025). ‘Tornar visível o invisível: o inquérito em História e a natureza do conhecimento histórico (Making visible the invisible: Historical enquiry and the nature of historical knowledge)’ In: Educação histórica: teoria e investigação empírica. Portugal : CITCEM-FLUP.

Onyancha, O. (2022). Indigenous knowledge, traditional knowledge and local knowledge: what is the difference? An informetrics perspective. Global Knowledge Memory and Communication 73(1). DOI:10.1108/GKMC-01-2022-0011

Wandersee, J., & Schussler, E. (1999). Preventing Plant Blindness. The American Biology Teacher, 61(1). https://doi.org/10.2307/4450624

Zani, G. & Low, J. (2022). Botanical priming helps overcome plant blindness on a memory task. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 81(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101808