In May 2025, EuroClio and Europeana welcomed six cultural heritage educators to The Hague for a co-creation session as part of ‘Creating Lessons with Cultural Heritage’. The project seeks to dive into the untapped wealth of cultural heritage available through museums, archives and other cultural institutions to create ready-to-use materials for the classroom.

During their stay, the educators co-created eLearning activities using the Historiana platform. Below, Stefania Gargioni shares her experience of working with digital cultural heritage and introduces her eLearning teaching activity.

- Link to the eLearning activity: http://hi.st/Brf

As part of EuroClio and Europeana’s ongoing commitment to using cultural heritage to foster critical historical thinking, I recently developed a new learning activity for Historiana that invites students to explore colonial history through subtle, visual evidence of power

dynamics.

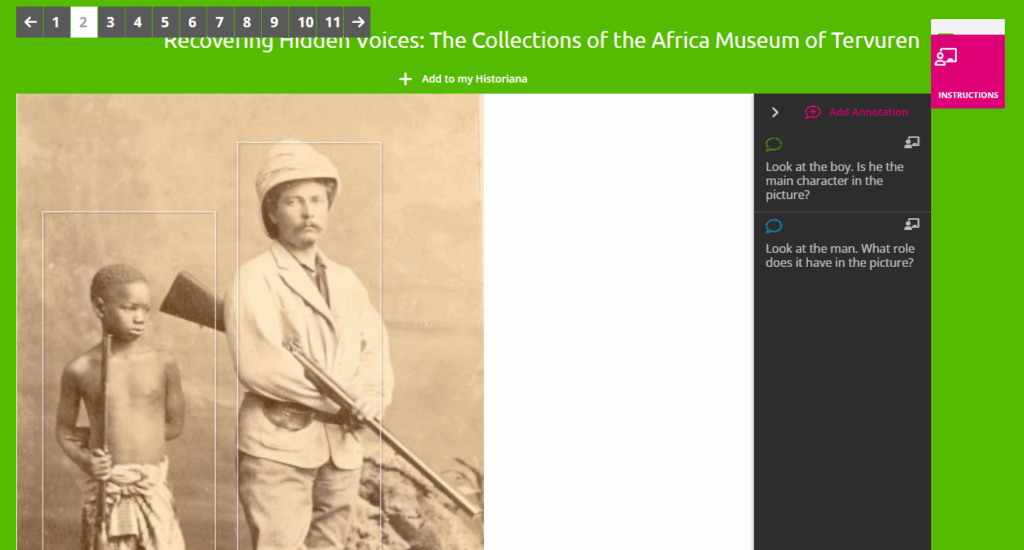

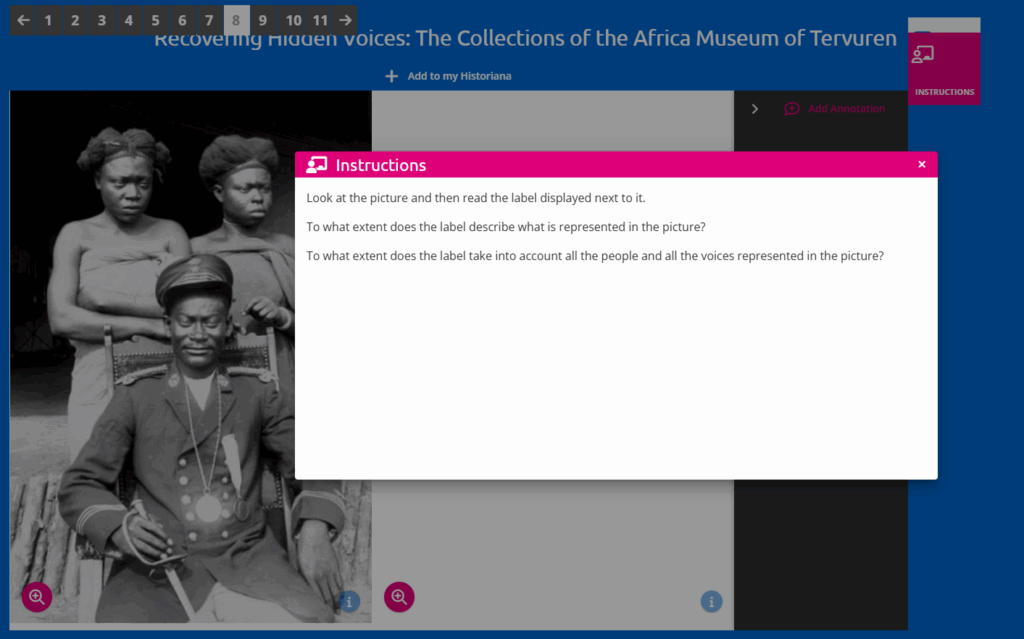

This activity draws on historical images from the collections of the Africa Museum in Tervuren, Belgium—a museum deeply intertwined with the legacy of Belgian colonialism in Central Africa. Rather than focusing on graphic depictions of violence, the activity highlights more understated portrayals of dominance: portraits, carefully staged group scenes, and photographs of everyday colonial life that, at first glance, may appear neutral or benign. These are the kinds of images often accepted uncritically, yet they silently convey messages about racial hierarchy, civilisation, and control.

Students are guided through a process of visual inquiry and comparative analysis. The activity is structured around a series of layered questions that help students deconstruct the images. The initial questions lead into deeper reflection on authorship, audience, and intended message. Students are encouraged to reflect on how institutions such as the Africa Museum have historically framed these collections. This raises essential questions about how cultural heritage is curated, and how the presentation of such images has contributed to particular understandings of colonial history. In this way, the activity prompts students to

engage not only with the past but also with the ways in which the past is remembered and displayed.

By working with digitised visual sources, students practice close observation, historical empathy, and ethical reflection. They are not just learning about colonialism as a historical process, but about its cultural dimensions—how it was justified, normalized, and perpetuated through visual media. The activity builds visual literacy alongside historical thinking, helping students recognise that even seemingly mundane sources are shaped by power and ideology.

This activity helps students uncover the hidden voices of colonisation—not through loud declarations, but through silences, absences, and the subtle framing of visual material. By closely analysing images that may appear neutral, students learn to detect whose stories are being told and whose are being left out. This process invites them to engage their inner voice as they respond to injustice, question dominant narratives, and reflect on how visual culture shapes historical understanding.

For educators, the activity offers a teaching strategy that foregrounds interpretation, critical inquiry, and ethical reflection. It encourages a shift from traditional content-driven instruction to a more dialogic, student-centred approach. Teachers become facilitators of meaning-making, helping students navigate ambiguity and develop historical empathy. By engaging with museum collections as constructed narratives rather than passive archives, both students and teachers learn to confront the legacies of colonialism and listen more carefully for voices that history has often marginalised or erased.

Ultimately, the goal is to develop students’ capacity to read images historically and ethically. They learn to interrogate sources critically and to question how historical narratives are constructed—not only in textbooks, but also in museums, archives, and cultural institutions. This aligns with Historiana’s mission to equip young people to become thoughtful, critical,

and engaged citizens.