Students encounter the past in a myriad of ways outside of the history classroom: family (hi)stories, commemorations, cinematic movies, TV programmes, social media, comic books, video games, you name it. We might call the approach in the classroom, based on academic methodology, ‘disciplined history’. The non-academic approaches could then be categorized as ‘undisciplined’. Disciplined and undisciplined histories are two parts of a wider historical culture, that may often be at odds with each other. Yet, they do occasionally meet, most notably in the history classroom.

Undisciplined images of the past are often engaging. When watching a good historical movie one may easily be swept up by it, identifying with the main characters, wanting to know how the story ends. Or we may listen to stories our grandparents tell us, fully interested in knowing how they have experienced the past and how their experiences have shaped our own lives. A lot of our students – and sometimes even we ourselves – feel part of the story that develops within a video game like Assassin’s Creed or Ghost of Tsushima. Students unconsciously take these images with them when entering our classrooms.

Yet, these same images are not necessarily based on sound historical research. They often do not entirely correspond with the understandings of professional historians. As history teachers we may be tempted to simply correct these images, replace their misunderstanding with academic consensus. Yet, we would argue that adding some extra layers before you focus on the academic consensus may keep students motivated. Furthermore, this may strengthen their sense of belonging and self-identification process. These undisciplined understandings of the past are meaningful to our students, perhaps even more meaningful than the historical consensus offered by historical textbooks. Ignoring these forms of history means missing an opportunity to really connect with what matters to our students.

One of the reasons our students find these undisciplined understandings meaningful is that they offer narrative understandings of the past that cohere with their core values and their fundamental worldviews. They tell stories that helps them understand how this world works and what is important. When a series like Vikings: Valhalla airs, we learn that there are people who are good and trustworthy and people who are not. We learn that justice is something to strive for, making perpetrators of evil pay for their misdeeds. Yet we also learn that change may be a force that disrupts our plans and that religion in itself is insufficient to make you a good person. Even if the specific historical facts are portrayed correctly–and this is sometimes not the case in Vikings: Valhalla–the narrative is effective because of its deeper meaning. To put it another way: undisciplined history works because it gives meaning to our lives, not because it is factual. To some degree we need these stories to lead meaningful lives.

Undisciplined history comes with its risks. For one thing, undisciplined narratives minimize the gap between past and present, often mirroring current concerns, values and worldviews more than past ones. Also, they seem to offer an often simplistic understanding of the past, lacking attention to multicausality and multiperspectivity. Getting stuck in an undisciplined understanding of the past may hinder us in truly understanding the complexities of our world.

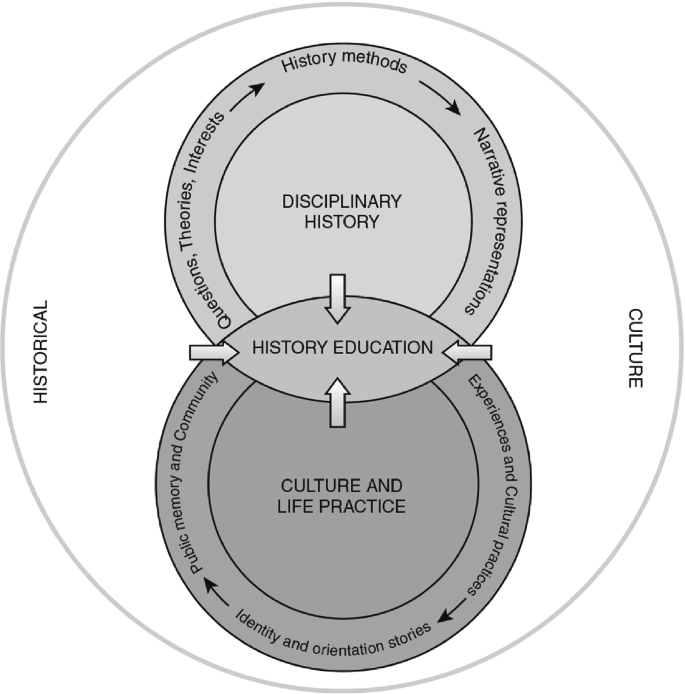

(Lévesque & Croteau, 2017)

Disciplinary history, on the other hand, may risk being meaningless. To train historical thinking skills often means to work deconstructively: to unravel sources and to create plausible, multiperspective and nuanced historical understandings. Narratives based on on such methodologies are often not as clear-cut as undisciplined ones. They offer more nuanced understanding of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ people in history, often interpreting historical actions based on the historical context of the time. They also seldom provide clear worldviews. Despite the risk of losing a sense of meaning in history, most modern curricula promote such methodological, disciplined thinking skill. One argument to do so is to strengthen critical thinking skills and citizenship education (although a long term effect of the teaching of historical thinkings skills and citizenship competencies has yet to be demonstrated to our knowledge).

We do believe that teaching disciplined thinking skills is important. We believe that without them people will be less likely to develop an autonomous and critical relationship with the past. Those who are not able to approach the past critically risk being swept up in rhetorical narratives merely aimed at strengthening political powers or economic interests. Also, an undisciplined understanding of history is often closely connected to the narrative perspective of the powerful, and therefore tends to disregard or even actively destroy historical perspectives of minority groups. A truly inclusive, multiperspective history education cannot exist without sound historical thinking skills.

Yet, how do we integrate the meaningful undisciplined narratives into a classroom based on disciplined history? We would suggest that those undisciplined histories form the perfect starting point for training these skills. Let us give you two examples that may help to accomplish this goal.

Family photos and stories

One way to use undisciplined history is to ask your students to bring a family photo to class. This should be a photo that they feel personally connected to. Preferably a photo from a prior generation, for example a photo of their parents being younger or a family home. In pairs you may ask your students to tell each other about that picture. First, you start off with questions that help describe what is depicted: ‘What do we see here?,’ ‘Where and when was this picture taken?,’ ‘Do you know the people in the picture?’ After students have described the picture, you may continue to let them narrate the story behind the picture: ‘What happened before and after this picture was taken?’ & ‘What caused the event and who was involved?’ As a third step you may then discuss the meaning of that narrative and therefore that picture: ‘What feeling do you get when you look at the photo and/or the story you told your classmates?,’ ‘Why is that?,‘ What does this photo say about your family members?,’ ‘Does this photo also say something about yourself?,’ ‘Why is it important that you keep this photo?,’ or ‘Does this photo also tell you something about how the world works? If so, what?’ Lastly, you may compare different photos and their stories in a classroom discussion: ‘Can we understand why this photo is so important to […]?’ You may also discuss how these stories relate to the text in the textbook; do they cohere to the narrative told there? If not, do they provide a new perspective? In what sense should we be careful in accepting new perspectives? How can these new perspectives also enrich our understanding of the past? It is in this last part of the classroom discussion that the undisciplined narrative may be connected to disciplinary thinking. In that way it may help improve those thinking skills.

Films & series

Another way to use undisciplined history is to use historical TV shows, streams or movies. This is something that a lot of teachers already use in their classrooms, but we would like to add a way to teach students how to contextualize a movie, not only from a historical perspective, but also from a current day perspective. In this assignment we will use Bridgerton as an example to further clarify some parts of the assignments.

First, let students watch a part of the TV show, movie or stream that you would like to discuss with the students. Second, select historical sources that are edited so that students understand them and gain historical context about a historical person similar to one or more characters in the tv show. Give them some historical questions that help them weave a context that is useful for the chosen subject. Think about questions that touch the political, socioeconomic, and cultural context of a historical era. In the case of Bridgerton, we chose to show the last part of the first episode of season one and let students contextualize ‘women in the Regency era.’ We developed questions like: ‘Which values and norms are important in society?’ or ‘In what way do people in society express themselves culturally?’ Third, let them do the same exercise only for current day people. In the case of Bridgerton, we chose the position of women in our current (Dutch) society. Lastly, you could discuss with the students which parts of the historical context and which parts of our current context are visible in the TV show and discuss why screen writers, directors, etc. choose this combination instead of a full historical context. That way, you pay attention to why they feel so connected to a TV show but also show them how to properly analyze the TV show historically.

Undisciplined history is not just for fun and disciplined isn’t just ‘the right way’. They are both part of the historical culture and need each other in the history classroom. Without disciplined history, students will easily believe every historical narrative that is thrown at them, but without undisciplined history, our students do not get the chance to identify and connect with the strange past.